Pablo Picasso in Music: “Formes en l’air” by Artur Lourié

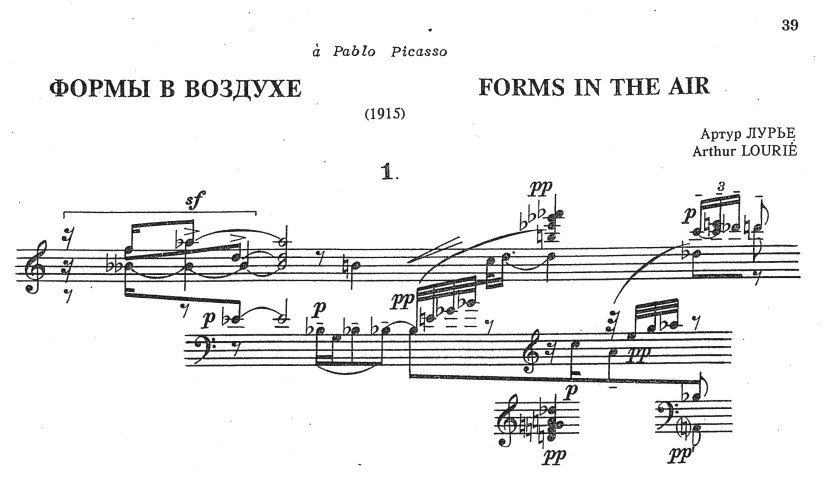

Have you ever imagined that a music score could look like this? Have you ever wondered why a composer would visualise in this peculiar way their musical thought? How can you possibly read this music score on which staves are not placed as usual? Arthur Lourié’s Formes en l’air (1915) is dedicated to Pablo Picasso: an artist Lourié admired for his artistic boldness. Contrary to Picasso, Lourié is a relatively unknown artist. However, while he was young, Lourié used to stand out for his musical creativity.

Who is Arthur Lourié?

Lev Bruni, Portrait of Arthur Lourié. 1915. The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Born in 1892 in St. Petersburg, Arthur Lourié was a Russian composer who lived in St. Petersburg, Berlin, Paris, and the United States. Lourié spent his youth in St. Petersburg where he was one of the leading composers of the Silver Age (c. 1890-1920). This was an exceptionally creative period in Russian art with many influences from European Symbolism. Silver Age Symbolists believed that various divisions between artistic disciplines were artificial: poetry was profoundly linked to painting, music, and drama. A few years before the 1917 Revolution, Lourié was known among the Symbolists for his rebellious artistic temperament. His sense of style earned him the reputation of a dandy, but he was also admired as a highly cultured man with wide ranging interests. Until the early 1920s, Lourié composed many musical works with references to other genres of art such as Sappho (1914) which is a song cycle of Ancient Greek poems written by Sappho, Formes en l’air (1915) which is an attempt to aesthetically link music for solo piano with Cubism in visual arts, and Verlaine (1919) a song cycle based on Paul Verlaine’s poems.

In 1921, Lourié emigrated to Berlin. In 1922, he moved to Paris where he befriended Igor Stravinsky. In 1941, he went to the United States where he stayed until his death in 1966. In America, Lourié was nostalgic for his early years in St. Petersburg; but he knew better than anyone that the Silver Age was a time that was gone. Today, Lourié is occasionally remembered; when he is, he is remembered for being forgotten.

Pablo Picasso and Cubism

Cubism (c. 1908-1914) was a movement in European visual arts which employed geometric shapes to depict human figures and other objects. Cubism was a revolutionary artistic approach to representing different views of the same figure or object at the same time. This is why very often figures are barely recognisable. Picasso once said: “A face is a matter of eyes, nose, and mouth which can be distributed in any way you like.”

Have a look at young Picasso’s photo below. It is from his Cubist period. Look at the shapes behind him. The more you stare at these shapes, the more you wonder about what they may picture. Sometimes, the outlines of these shapes are so subtle that they are recognisable only thanks to the different contours Picasso has used. If we could see the colours of this painting, do you think that the different shades would help us imagine the outlines of these shapes?

Portrait photograph of Pablo Picasso, in front of his painting The Aficionado (Kunstmuseum Basel) at Villa les Clochettes, Sorgues, France, summer 1912. RMN-Grand Palais. Wikimedia Commons

Also, in his cubist style, Picasso was inspired by African tribal masks which are highly stylised. Thus, these masks have considerable differences and at the same time considerable similarities with real-life human faces. The inspiration from a non-Western civilisation was something Picasso and Silver Age Symbolists in Russia had in common: Russian Symbolists incorporated into their art elements that reminded them of primitive civilisations (for example, the Scythian civilisation, an ancient Eastern Iranic nomadic people).

Formes en l’ air

The name of this piece for solo piano is intriguing: Formes en l’air, “Shapes in the Air.” It makes us wonder how Lourié outlines the musical forms to structure his musical thoughts. Picasso uses different contours to outline the shapes in his Cubist paintings. Lourié does something similar: Observe the symbols f (forte= play loudly), pp (pianissimo= play quietly), and ppp (pianississimo= play more quietly). You will see that Lourié puts these indications in a way that shows to the pianist that they have to play together these sounds. These delicate nuances of sound are the equivalent of the different colour shades Picasso used in his Cubist paintings to outline the shapes of the figures he drew. Indeed, the title Lourié chose, Formes en l’air, is very creative: he does not use any of the traditional musical forms to express himself musically. Instead, he borrows Picasso’s expressiveness in visual arts and tries to translate it into music.

What I find the most fascinating about Lourié’s Formes en l’air is that you do not need to be able to read musical notation to understand how Lourié depicts his artistic thought in the score. While you listen to Formes en l’air, Picasso’s shapes and colours pop into your head and you just have to wonder how Lourié depicts with sounds anything that a painter would depict with shapes and colours. The more I look at the score, the more associations I find with Picasso’s Cubism. What do you think? Listen to this piece, follow Lourié’s musical thoughts on the score, and do exactly what Picasso and Lourié want you to do: Let your imagination fly!