Let’s Get Corny: Grant Wood’s Portrait of Rural America

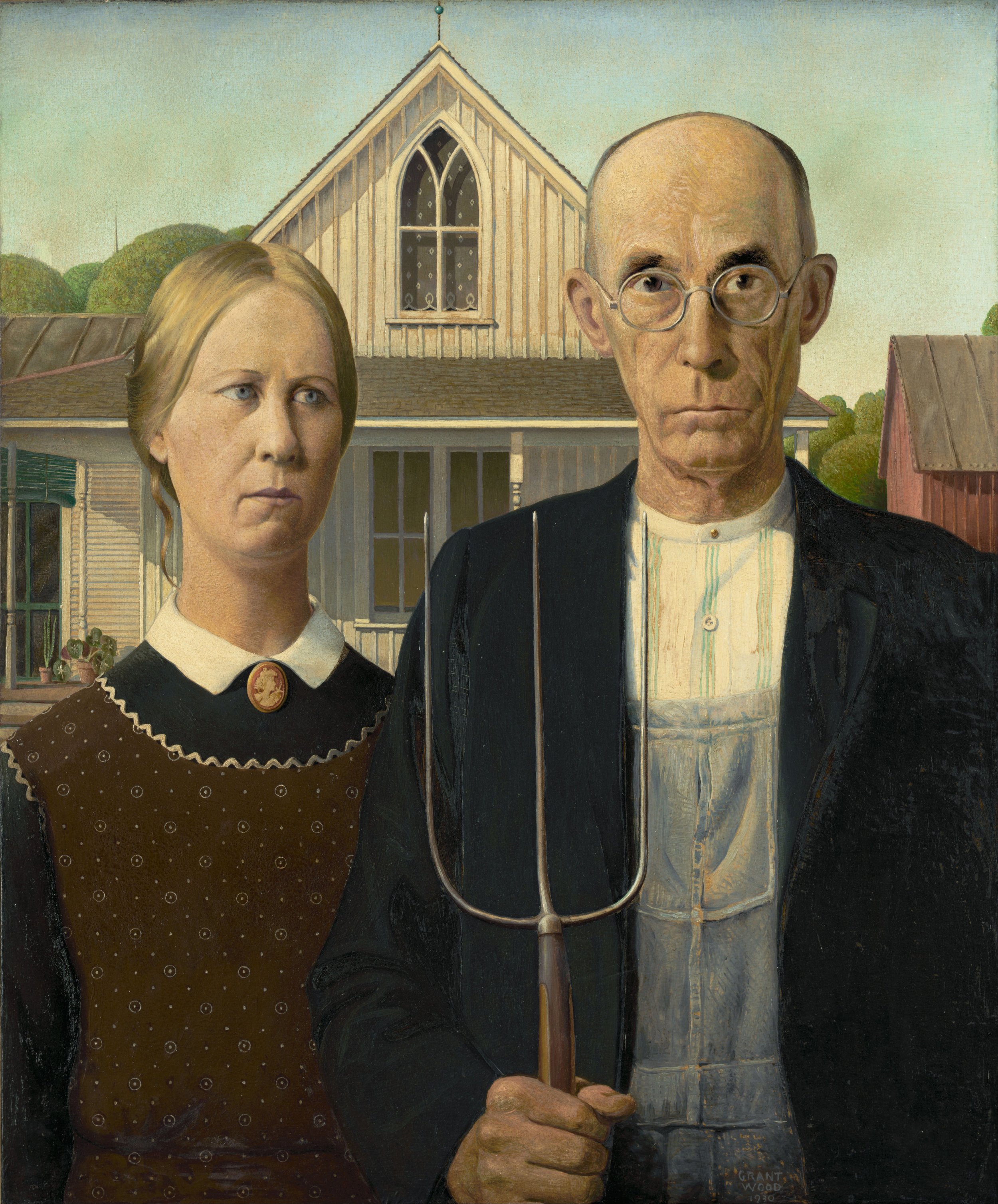

Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930), oil on beaver board. 78 × 65.3 cm (30 3/4 × 25 3/4 in.). Located at the Art Institute of Chicago. WikiArt.

Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” is so famous that sometimes it’s hard to remember if you’re picturing the painting as it actually is, and not one of its countless homages and spoofs. Its composite elements – the man and woman, the pitchfork, the Gothic window in the background, and the grim expressions – are each iconic in their own right. Each one could be the entire story. Which might explain why no one can actually put their finger on what the actual story is. And so the painting itself becomes a kind of allegory for whatever people want it to mean, all across the America of its title. It’s a bleak satire of the American dream. And it’s a wistful celebration of a disappearing way of American life. It’s a portrait of “pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers,” as the critics said at the time, much to the dismay of Iowans. And it’s a portrait of the pioneer spirit, resilience, and nostalgia.

In times like this, it can be helpful to actually ask the artist what he meant. And Grant Wood was happy to tell us. He was born in Iowa in 1891, working as both a professional artist and art teacher, and until “American Gothic” he had never achieved much success outside the state. But he noticed that, for all the artists in the middle of the 20th century who sought to tell the story of America – Edward Hopper, Ansel Adams, Robert Henri, Robert Frank, and innumerable others – very few were showing much love to the Midwest. Wood painted “American Gothic” to submit it to a painting competition at the Art Institute of Chicago (it took home bronze, along with a $300 cash prize), with the explicit aim to create a narrative of Iowa that wasn’t a caricature, but meant to show deep affection for its subjects. His figures have a stateliness and dignity that he had felt embodied in the men and women he had grown up around. And he wanted, in particular, to paint them as he had seen artists in Paris paint portraiture. He had made a number of trips to Paris earlier in his life, studying Flemish altarpieces, Medieval portrait sculptures, and French Impressionism. And now he wanted to bring them home. In his words, “I had to go to France to appreciate Iowa.”

These trips to France are probably what also trained his eye to recognize the Gothic-style window in a house he had passed, which originally inspired the entire painting. It was a small, white house, now called the Dibble House after its first owner, Charles Dibble, which was built in what was called the Carpenter Gothic style. This is a uniquely North American style, borrowing characteristics like pointed arches and steep gables somewhat loosely from the Medieval period, and then adding decorative motifs like gingerbread trim and other jig-sawn details, thanks to the recent invention of the steam-powered scroll saw. In other words, this was an homage to a Medieval style that had been greatly updated with modern technology. The overall aesthetic meant to evoke both quaintness and nostalgia and, maybe inversely, classy European ornamentation to what was otherwise a straightforward flimsy Midwestern frame farmhouse.

Wood sketched the house on the back of an envelope and then set forth to determine the kind of couple who would live there. He recruited two people in his real life that would serve as stand-ins for the man and woman of the house: his sister, Nan, and his dentist, Dr. Byron McKeeby – both of whom, with their long faces, the pitchfork, and even the stripes and stitching of their clothes, reinforce the Gothic aesthetic of verticality and height. Whether or not Wood meant for them to be husband and wife or father and daughter is actually a source of debate; he has letters where he described both options, and most likely settled on father and daughter due to some harsh criticism of the painting regarding how much older the man seemed than the woman.

But no matter what their relationship, they are surely wedded by the fact that they both seem completely miserable. Yet you still see where Wood attempted to give them each their dignity. For all the woman’s despondence, she does have a beautiful broach and a saucy little lock of hair that’s escaped her bun. The man’s hand grips the pitchfork with resolute strength – compositionally, he keeps the entire painting upright. Thomas Hoving, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the painting’s biographer, tells an anecdote about Wood’s relationship with his dentist, having been plagued with gum problems his whole life, and how he was forced to spend many trusting hours in a dentist’s chair staring up at this long, bespectacled face with deep affection. “There is satire in [the painting],” Wood wrote, “but only as there is satire in any realistic statement. I tried to characterize them truthfully – to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life.”

But the truth is, it doesn’t always matter what the artist intended. When paintings become so famous that they take on a life of their own, the larger cultural meaning can force the artist’s intentions into the backseat. And throughout the lifespan of this painting, the cultural view of rural America has undergone a number of changes. There have been moments where a painting like this, intentionally contrasting the soot-covered, fast-paced, alienating modern cities with rural nostalgia, was valorized by American culture, and was even propped up as a unifying image. After all, the background set design all along the yellow brick road in 1939’s The Wizard of Oz is modeled after Wood’s paintings, a view of America that Americans, post-Depression and pre-war, were proud to share.

Of course, we’re in a different moment today. We’ve had a different depression; we’re fighting different wars, both international and domestic. And so, it’s been much easier to dismiss Wood’s portrait as a part of America that a whole other side chooses not to respect. This kind of polarization might take generations to repair, but a good starting point might be this very painting – not only for its multiple interpretations, depending on the perspective you take, but also for its deep, deep love of one’s home. That’s simply something you’re never going to argue someone out of. There’s no place like home, and no one understood that quite as well, and with more dignified nostalgia, as Grant Wood.